Anyone who saw the Oppenheimer movie knows the story: In response to German government actions against groups such as Jews and suspected Communists, a number of the country’s physicists left, primarily for the United States, starting in 1933. That scientific diaspora helped the US Manhattan Project develop an atomic bomb before competing countries such as Germany and Japan, which in turn helped the US not only win the war, but also become a world power on earth and in space.

Ironically — given that some members of the government have called for an AI Manhattan Project — the US may be heading down the same path as 1930s Germany.

It’s too soon to tell whether current US actions will have the same effect on AI research, but some other countries are salivating at the opportunity. The result could make it more difficult for the US to maintain its AI lead over China.

What Makes the US Less Welcoming to AI Researchers?

“It's not so much as contemplating to leave but more of a contingency plan if things go further south."

- Leo Anthony Celi

Senior Research Scientist, MIT

AI researchers fall into three main categories:

- Born in the US and working in the US

- Born outside the US and currently working in the US

- Born outside the US and considering working in the US

The Trump administration has taken a number of actions since coming back into power that make working in the US less attractive to members of all three groups, for different reasons.

Most significant for foreign-born researchers have been Administration efforts to curtail immigration — particularly for China.

“Under President Trump’s leadership, the US State Department will work with the Department of Homeland Security to aggressively revoke visas for Chinese students, including those with connections to the Chinese Communist Party or studying in critical fields,” the US State Department announced in May. “We will also revise visa criteria to enhance scrutiny of all future visa applications from the People’s Republic of China and Hong Kong.”

It was not clear whether AI would be considered a “critical field,” or when this might happen, and the State Department wouldn’t elaborate. But given that China is the main challenger of US hegemony in AI, it wouldn’t be surprising.

Other US actions toward immigrants and legal foreign-born residents also may make foreign-born researchers less comfortable with staying in or coming to the US, either in protest of the Administration’s actions toward immigrants, or because they are personally concerned.

In addition, the US has eliminated or frozen a number of research grants, particularly those that touch on topics such as diversity, equity and inclusion. Some of those grants were related to AI, such as freezing one that was intended to teach health AI to inner-city students, said Leo Anthony Celi, a senior research scientist at MIT.

Without those grants, existing researchers leave, and potential researchers may be dissuaded from pursuing study in the US. For example, in a New York Times article about research cuts, one reader noted that their US-born daughter had decided to pursue an AI PhD abroad.

And she’s not alone. “It's not so much as contemplating to leave but more of a contingency plan if things go further south,” Celi said. “I know a lot of us are putting together contingency plans.”

Related Article: Where the US Stands in the Global AI Race

Countries Laying Out the Welcome Mat for AI Researchers

At the same time, other countries are creating programs intended to attract researchers leaving or not going to the US. While many of those programs are about research in general, some are specifically geared toward attracting AI researchers.

For example, Norway recently created a program to attract researchers from outside Europe. “The initiative has a total budget of NOK 300 million [about $30 million US) and is expected to support the recruitment of 30–40 researchers to Norway,” said Anne Kjersti Fahlvik, executive director for innovation in industry and the public sector at the Research Council of Norway. “It is open to researchers from all academic fields, including AI. The background for the scheme is the difficult situation that many researchers and institutions are now experiencing globally.”

What makes Norway particularly appealing to AI is that the country recently allocated NOK 1.2 billion (about $120 million US) to establish six national research centers focused on AI.

“These centers will explore how AI affects society, develop the technology and strengthen innovation and value creation in both the private and public sectors,” Fahlvik said. “The centers will collaborate with leading international research environments in many countries, including the US.” Those centers plan to recruit more than 100 national and international PhD students, postdocs and researchers in 2026, she said.

Other countries creating programs to attract AI researchers include Germany, India and Slovenia.

What Will Happen to US AI Research?

Whether it’s fewer native-born US researchers staying, foreign-born US researchers leaving or foreign-born US researchers choosing to work in another country instead of the US, the result could be fewer US AI researchers overall — and more in other countries competing with the US in AI research.

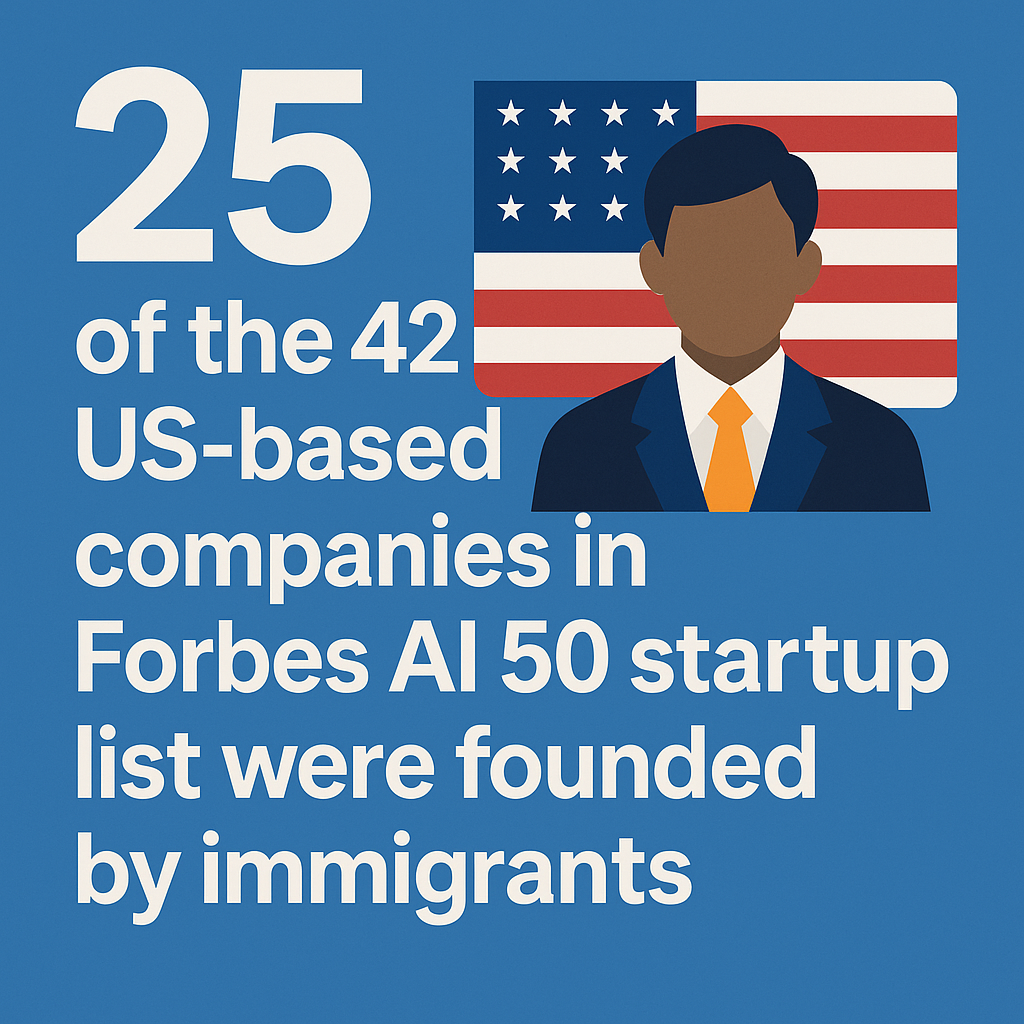

That’s a problem. According to the Institute for Progress, a nonpartisan think tank focused on immigration policy, 25 of the 42 US-based companies in Forbes AI 50 startup list were founded by immigrants. A 2020 Georgetown University study found that 72% of the founders from Forbes’ 2019 list originally came over on student visas.

One potential beneficiary is India. Because it’s becoming more difficult to convert an H1B visa to a permanent resident “green card,” some Indian researchers are returning from the US, wrote S. Yash Kalash, research director of digital economy at CIGI, the largest think tank in Canada. Others are returning because they feel disconnected from US society and want to return to their roots. “India has a strong startup culture, with the third-largest number of ‘unicorns’ [billion-dollar companies] after the US and China,” he said.

Another beneficiary could be the European Union — which already attracts many non-European students, but who return home after their studies. “Europe never had a talent attraction problem,” said Catherine Schneider, a policy researcher in AI and labour markets for Interface, a Berlin-based nonprofit think tank that studies technology and society. “The challenge for Europe is not bringing them, but keeping them in the region.”

Schneider has heard anecdotal reports about AI researchers in the US putting out feelers. A number of the people in the AI field are female, gender nonconforming or have families, who are concerned about US culture and the quality of life, she said. “It’s not just that women are looking at exits, but people are broadly looking,” she said. “We’re hearing from contacts that there’s more applications to professorships,” including from top US universities.

But the biggest beneficiary of all could be China. Dan Hendrycks, director of the Center for AI Safety, and one of the primary opponents of a “Manhattan Project for AI,” claimed in several podcasts, including the No Priors podcast, that as many as 30% of the employees at leading AI companies were Chinese nationals. If those companies divested themselves of Chinese employees, they’d likely return to China. The same could likely be true if the US were to follow through with its threat to cancel Chinese visas.

Chinese nationals are important for US AI success, Hendrycks said. In its attempt to protect itself, the US could be shooting itself in the foot.